It sounds a little like the latest sequel in a gripping fantasy adventure series, in which the plucky BYOD battles hordes of evil forces on his quest to gain some unlikely artifact, the hand of his beau, and a wonderful story to tell the grand-kids. But “BYOD” and the “Internet of Things” are two growing areas of security concern for organisations, linked conceptually by the commoditisation of information processing hardware. In this article we’ll explore these twin faces of a shared underlying technological zeitgeist, the risks posed for organisations, and how vulnerability scanning using a solution such as AppCheck can help protect your organisation from these risks.

In 1965, Gordon Moore – co-founder of Intel – postulated that the number of transistors that can be packed into a given unit of space will double about every two years. The prediction has been quoted almost continuously ever since – largely due to its uncanny accuracy – and has become known as “Moore’s Law”. A more commonly and loosely interpreted version of the original prediction simply states that we can expect the speed and capability of our computers and other electronic devices to increase every couple of years, and we will pay less for them.

And this is exactly what has happened. As transistors in integrated circuits became more and more efficient over the last six decades or so, computers become smaller and faster, to the extent that the boundary between “computer” and “device/appliance” became increasingly blurred. It became practical and cost-effective to embed serious information processing within devices such as cars, stereos, mobile devices and smartphones, tablets, GPS units, cameras, fridges and more.

At the same time as computing power has grown smaller and more embeddable, we’ve also seen a drastic increase in the interconnectedness of devices. It no longer seems in any way unusual for us to have a device in our pocket – or on our wrist – that is hooked into and able to communicate with a network that spans the globe, or for us to connect our fridge, central heating, CCTV cameras or air conditioning units to this same global network.

Science fiction frequently makes reference to the potential of a technological singularity, a hypothetical future point in time at which technological growth becomes uncontrollable and irreversible, resulting in unforeseeable changes to human civilization. We’re not exactly there yet, but the challenges presented by the realisation of a modern era containing computing devices that are both massively interconnected and extremely miniaturised and portable is definitely with us, bringing both challenges and benefits.

The promised advantages of ever-smarter, smaller and more ubiquitous computing technology includes the ability to help keep us all healthier, safer, and more productive, but there are also growing concerns around privacy and security. In this article, we’ll look specifically at the twin aspects of “BYOD” and the “Internet of Things”, both of which we’ll define and explore below, and the security risks that they present for organisations.

The “Internet of Things” is the term given to the growing network of interrelated computing devices and mechanical and digital machines that have the ability to transfer data over a network without requiring human-to-human or human-to-computer interaction. Consumer, commercial and industrial applications all exist, from commodity sensors, embedded systems, to control systems, automation (including home and building automation), and others. In the consumer market, the technology mainly pertains to the concept of the “smart home”, covering devices and appliances such as lighting fixtures, thermostats, home security systems and cameras that as well as interconnected “input” devices such as smartphones and smart speakers. Security is a major concern in adopting Internet of Things technology, with concerns that rapid development is happening without appropriate consideration of the profound security challenges involved.

As well as these fixed devices, the commoditisation of hardware means that there’s a partnering proliferation of smart, networked mobile devices. Personal devices containing significant compute power and the ability for near-field, local, or area wireless communication now includes not only relatively “visible” devices such as personally-owned tablets and laptops, but also smartphones and “wearable tech” such as smart watches and even smart rings.

The phenomenon of “BYOD” (Bring Your Own Device) loosely describes the growing acceptance of the reality of such devices within organisations and corporate premises and networks – either as officially permitted devices for the conduct of work, or permitted personal devices that may connect to corporate network infrastructure.

The risks posed by BYODs and the Internet of Things are substantial and challenge the paradigms that many organisations’ security model is based on. Many of the technical security concerns are similar to those of conventional compute equipment such as servers, workstations and corporate-issued smartphones, and include common vulnerabilities such as weak authentication, forgetting to change default credentials, unencrypted messages sent between devices, and poor management of security updates. However the twin threats posed by BYODs and the Internet of Things also introduce substantial new risks and attack vectors for organisations. We’ll take a look at some of the more often-quoted risks with these emerging technologies below

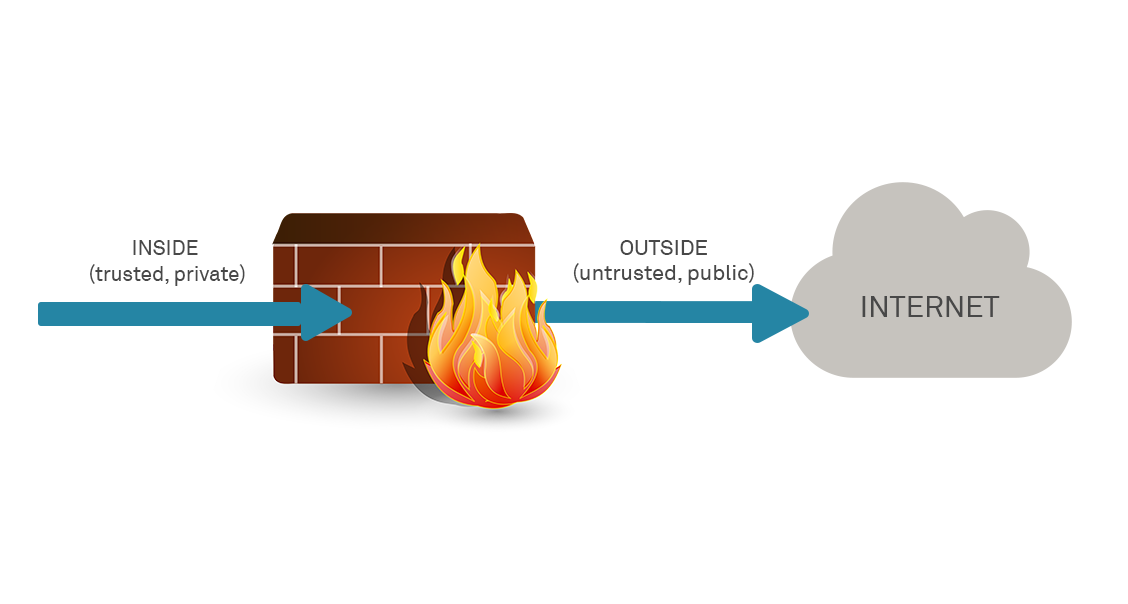

It used to be the case that, at least in theory, an organisation could be neatly segregated into a trusted, internal network and an untrusted external network.

This has always been an over-simplification of course, but as an essential model did hold essentially true in the dawn of computer networking, to some extent at least. In the modern era, the model has been seriously challenged as accurate in any way to describe modern corporate network challenges, but the twin threats of BYOD and the Internet of Things disrupt the model almost completely:

The low price and consumer focus of many devices deployed means that devices deployed are unlikely to have been designed as securely or with anything other than purely functional concerns considered. This can mean that even basic security measures such as transport encryption for authentication transfer, or per-instance passwords for access (rather than single hard-coded password) are not implemented, leaving the devices wide open to compromise by attackers.

Internet of things devices also have access to new areas of data and can often control physical devices and systems. They may take as input either sensed data, user inputs, or other external triggers (from the Internet) and command one or more actuators towards providing different forms of automation. Buggy apps, unforeseen bad app interactions, or device/communication failures, can cause unsafe and dangerous physical states when instructions are issued – for example devices may instruct a smart-lock to simply unlock under certain error conditions or power failure, a risk simply not present with a physically keyed lock. Worse, the devices may be potentially able to be subverted at will by attackers, causing malicious damage such as instruction a server air conditioning unit to start pumping out hot rather than cold air.

Unlike corporate-issued devices there is often no quality gate on devices before they are introduced to the corporate network or environment. The organisation does not, by definition, control BYODs and cannot ensure that even rudimentary security has been enforced on the devices.

With more and more systems and software, plugins and apps, organisation will continue to be challenged with keeping everything updated and patched. The problem is exacerbated by factors including:

• Lack of control of patching on BYODs;

• Low price and consumer focus of many devices also typically makes a robust security patching system uncommon;

• A proliferation of device management interfaces and systems leading to an incredibly complex estate to track and manage; and

• BYODs that are not persistent on network so cannot be tracked, scanned and patched consistently.

Many Internet of Things and embedded devices have severe operational limitations on the computational power available to them for cost reasons and are rushed to market as soon as a full functional set within a commercially viable form factor can be achieved. These constraints often make the devices unable to directly use basic security measures such as implementing firewalls or using cryptographic systems to encrypt their communications with other devices.

Hopefully it is clear from the above that BYODs and systems deployed under the “Internet of Things” umbrella create some clear challenges for effective security management. Next, we’ll look at how these devices can potentially be subverted by attacks and the issues that this can lead to for organisations.

Modern smartphones and CCTV cameras both generally offer at a minimum video and potentially audio transmissions and recording. They can therefore be used, either by the owner or by a malicious attacker who is able to subvert them, to perform covert recording of facilities and individuals without their knowledge, for purposes of surveillance, espionage, blackmail or extortion.

Poorly secured Internet-accessible devices can also be subverted to attack others, when attackers subvert the devices and then enrol them into a slaved device as part of a compromised “botnet” of many such devices. In 2016, a distributed denial of service attack powered by Internet of things devices running the Mirai malware took down a DNS provider and major web sites. The Mirai Botnet had infected roughly 65,000 Internet Of Things devices in under a day, a number that eventually increased to around 300,000 infected devices.

Perhaps most primitively but effectively, devices subverted can cause physical damage and destruction where they are hooked into commercial or industrial control systems. Examples include fire suppression system that are instructed to deploy, causing water damage, to air conditioning equipment in data centres of machine rooms that is instructed to run in heat rather than cool mode, potentially causing machine overheating and/or fire.

BYOD and the Internet Of Things are both serious threats to organisational security models, and ones that require a multi-faceted approach that includes network access control (NAC) or device registration, mobile device management (MDM), supplier due diligence and review, thorough network segmentation measures, proactive patching of all devices, and a robust vulnerability scanning regime that covers both web and application vulnerabilities across your entire estate. You likely can’t code review your new smart fridge or CCTV system, but you can scan it for vulnerabilities.

AppCheck help you with providing assurance in your entire organisation’s security footprint. AppCheck performs comprehensive checks for a massive range of web application vulnerabilities from first principle to detect vulnerabilities – including cryptographic weaknesses – in in-house application code. AppCheck also draws on checks for known infrastructure vulnerabilities in vendor devices and code from a large database of known and published CVEs. The AppCheck Vulnerability Analysis Engine provides detailed rationale behind each finding including a custom narrative to explain the detection methodology, verbose technical detail and proof of concept evidence through safe exploitation.

As always, if you require any more information on this topic or want to see what unexpected vulnerabilities AppCheck can pick up in your website and applications then please get in contact with us: info@localhost

No software to download or install.

Contact us or call us 0113 887 8380

AppCheck is a software security vendor based in the UK, offering a leading security scanning platform that automates the discovery of security flaws within organisations websites, applications, network and cloud infrastructure. AppCheck are authorised by the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) Program as a CVE Numbering Authority (CNA)